Your metabolic age is an important indicator of how well your body is functioning compared to your actual age. While your chronological age marks the passage of time, your metabolic age reflects how efficiently your metabolism is functioning.

It’s influenced by factors like your diet, exercise, and overall health. In this article, we’ll explain what metabolic age is, how it’s calculated, and share simple tips to help you improve it for better health.

What is Metabolic Age?

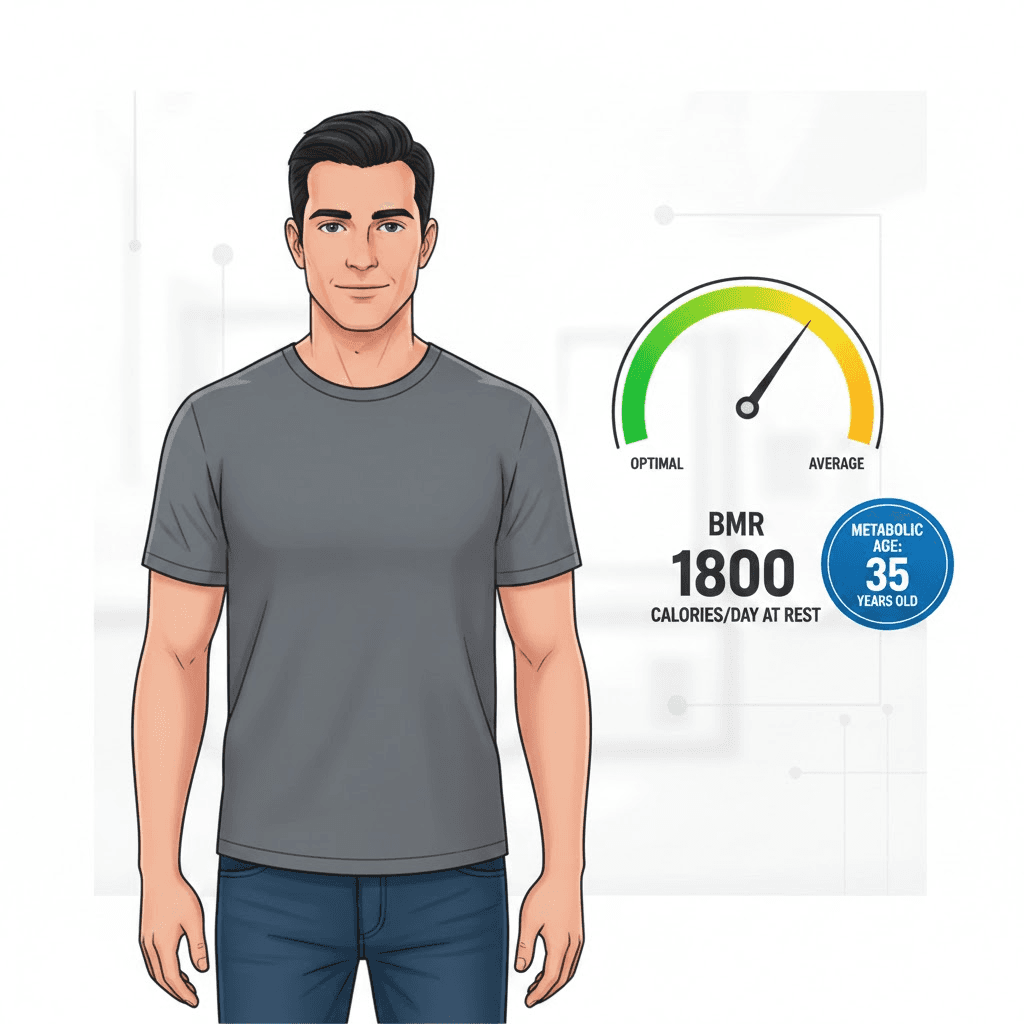

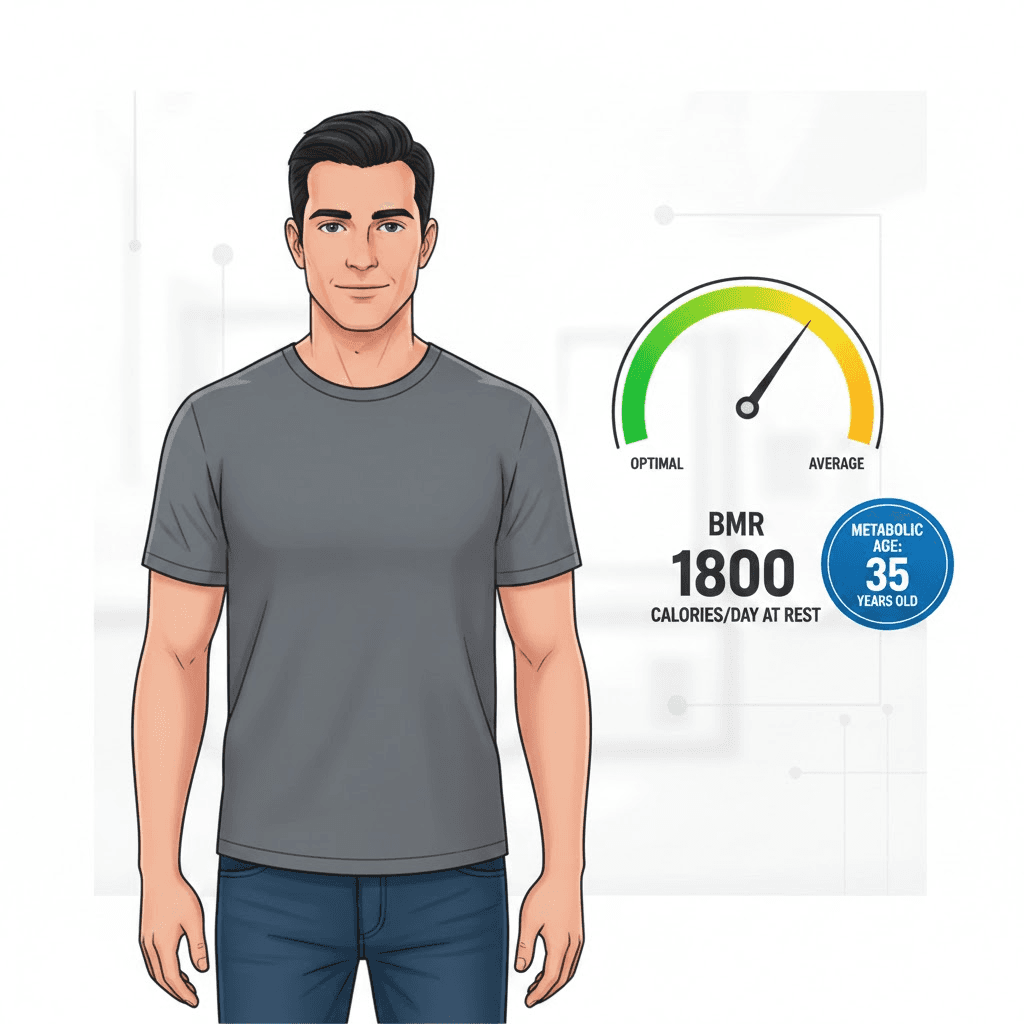

Metabolic age is a comparison between your basal metabolic rate (BMR) and the average BMR of people in your chronological age group. In simpler terms, it tells you whether your metabolism is performing like that of someone younger, older, or right around your actual age.

Your basal metabolic rate represents the number of calories your body needs to perform basic life-sustaining functions while at rest (e.g., breathing, circulating blood, producing cells, and maintaining body temperature). It's essentially your body's baseline energy expenditure, accounting for roughly 60-75% of your total daily calorie burn.

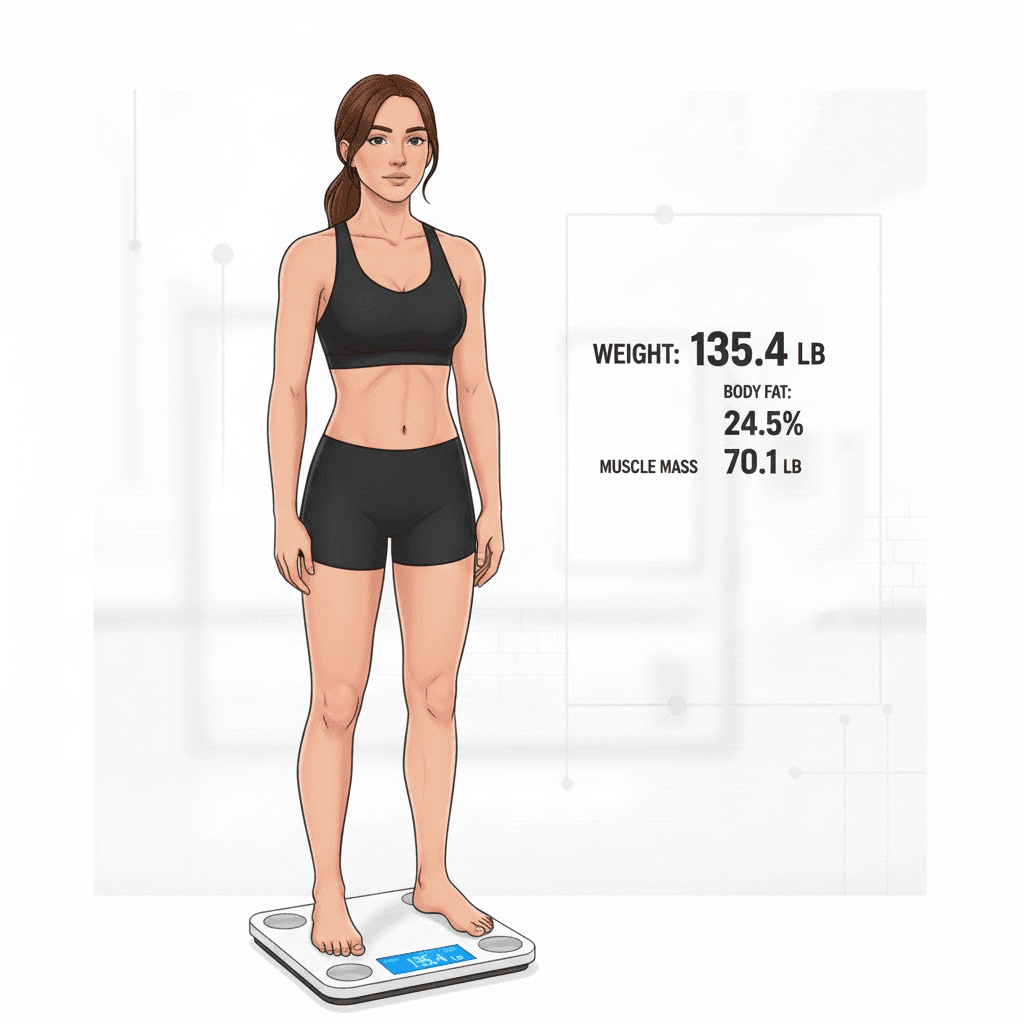

When health professionals or body composition scales calculate your metabolic age, they're measuring your BMR and comparing it against population data. If your BMR is higher than average for your age group, you'll have a lower metabolic age. If it's lower than average, your metabolic age will be higher than your chronological age.

Here's a practical example:

Let's say you're 45 years old, but your BMR matches the average BMR of a typical 35-year-old. Your metabolic age would be 35. Conversely, if your BMR matches that of a 55-year-old, your metabolic age would reflect that higher number.

The concept emerged from research into body composition and metabolic health, particularly as scientists recognized that chronological age alone doesn't tell the full story of someone's health status. Two people born on the same day can have vastly different metabolic profiles based on their lifestyle choices, genetics, and overall health.

It's worth noting that metabolic age isn't a standardized medical diagnostic tool in the way blood pressure or cholesterol levels are. Different devices and calculations may produce slightly different results because there's no universal formula or database. But, the underlying principle remains consistent: comparing your metabolism to population averages gives you a snapshot of your metabolic health relative to your peers.

What Metabolic Age Really Means for Your Health?

Your metabolic age can be a helpful reference point for understanding metabolic health trends, but it should be interpreted alongside other health markers.

Research suggests metabolic health is associated with longevity and lower risk of chronic conditions.

When your metabolic age is lower than your chronological age, it generally suggests several positive health markers. You likely have more lean muscle mass and less body fat, particularly visceral fat. Higher muscle mass increases your BMR because muscle tissue is metabolically active, meaning it burns calories even when you're sitting on the couch.

A younger metabolic age also typically indicates better insulin sensitivity, which means your body efficiently processes glucose and maintains stable blood sugar levels. This is often associated with better blood sugar control and cardiometabolic markers. Studies have shown that people with better metabolic health tend to have lower inflammation markers, healthier cholesterol profiles, and better blood pressure readings.

On the flip side, if your metabolic age is higher than your chronological age, it may reflect patterns such as higher body fat, lower muscle mass, or both. Research has linked a higher metabolic age to greater cardiometabolic risk, including higher risk of cardiovascular disease and future cardiovascular events. This is not a diagnosis, but it can be a useful signal to review lifestyle factors like activity, nutrition, sleep, and stress.

Metabolic Age vs. Chronological Age: What's the Difference?

Chronological age is the number of years since you were born. Metabolic age, by contrast, is dynamic and changeable.

You might be chronologically 50 but metabolically 40 if you've maintained excellent fitness, preserved muscle mass, and kept your body fat in check. Alternatively, a sedentary 30-year-old with poor dietary habits might have the metabolism of someone in their 40s or 50s.

The gap between these two ages reveals something critical: biological aging doesn't proceed at the same rate for everyone.

One significant advantage of focusing on metabolic age rather than chronological age is that it shifts attention to factors you can control. You can't change when you were born, but you absolutely can influence your metabolic health through daily choices. This perspective empowers you to take ownership of your health trajectory.

Aspect | Chronological Age | Metabolic Age |

Definition | The number of years since you were born. | A measure of how efficiently your body is functioning based on metabolism. |

Changeability | Fixed and unchangeable. | Dynamic and can change based on lifestyle, fitness, and health choices. |

Influencing Factors | Cannot be influenced. | Can be influenced by diet, exercise, muscle mass, and body fat. |

How is Metabolic Age Calculated?

The calculation of metabolic age involves several steps and requires specific body composition data. While the exact algorithms vary between devices and calculation methods, the fundamental process follows a similar pattern.

Step 1: Determining Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

First, your basal metabolic rate (BMR) needs to be determined. BMR is the number of calories your body needs at rest to perform basic functions like breathing and maintaining body temperature.

There are several ways to measure or estimate BMR. The gold standard is indirect calorimetry, which measures oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production to precisely calculate energy expenditure. However, this method requires specialized equipment and is typically only available in research or clinical settings.

Step 2: Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA)

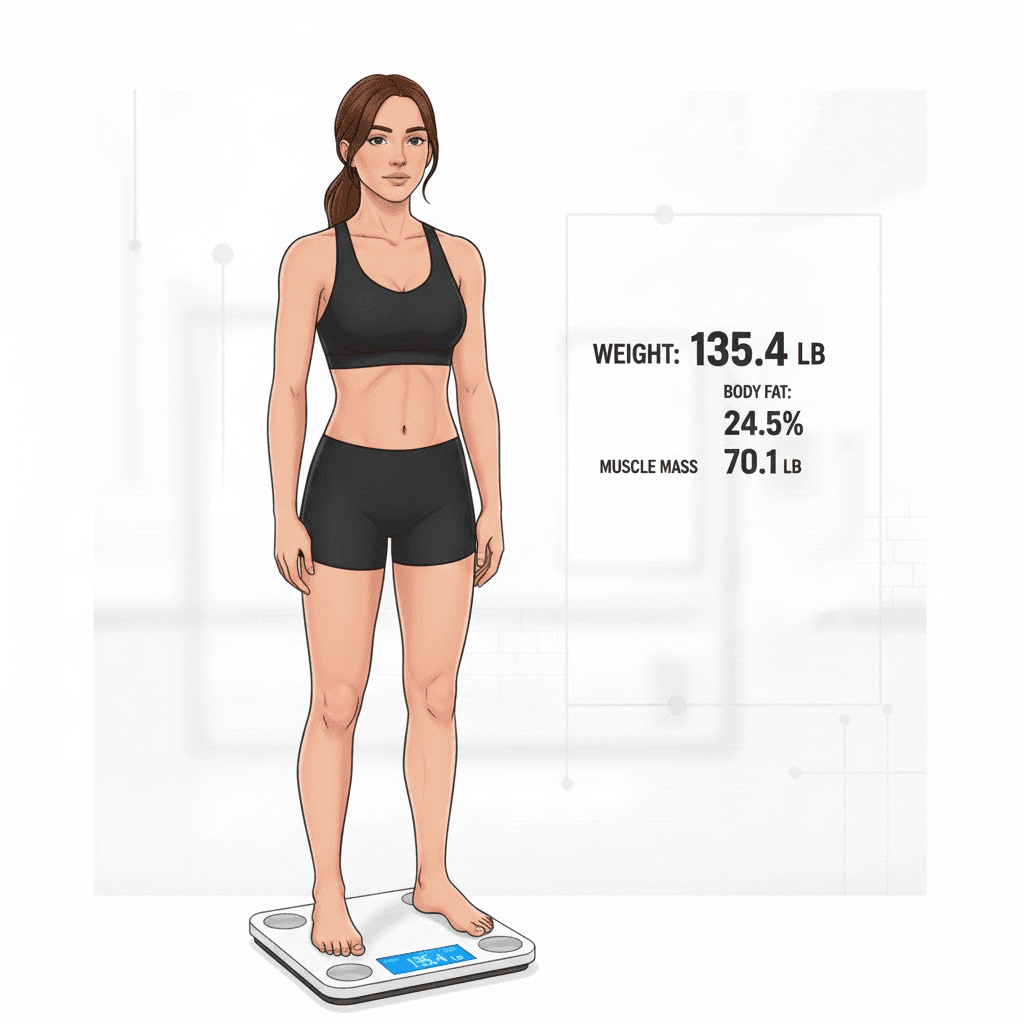

More commonly, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) devices estimate your body composition by sending a weak electrical current through your body. Since muscle and fat conduct electricity differently, the device can estimate your percentages of muscle mass, body fat, bone density, and water content. Many modern smart scales and body composition analyzers, such as InBody devices, use this technology to provide BIA-based estimates.

Step 3: Calculating BMR Using Mathematical Formulas

Once your body composition is known, mathematical formulas calculate your BMR. Several equations exist for this purpose, including the Harris-Benedict equation, the Mifflin-St Jeor equation, and the Katch-McArdle formula. These formulas consider variables like weight, height, age, sex, and lean body mass.

For example, the revised Harris-Benedict equation calculates BMR as:

For men:

BMR = 88.362 + (13.397 × weight in kg) + (4.799 × height in cm) - (5.677 × age in years)

For women:

BMR = 447.593 + (9.247 × weight in kg) + (3.098 × height in cm) - (4.330 × age in years)

The Katch-McArdle formula, which incorporates lean body mass, often provides more accurate results:

BMR = 370 + (21.6 × lean body mass in kg)

Step 4: Comparing BMR with Age Group Databases

Once your BMR is calculated, it’s compared against a database of average BMR values for different age groups. This database typically includes BMR data collected from thousands or millions of people across various ages. The comparison reveals where your metabolism falls on the spectrum.

If your BMR equals the average BMR for 35-year-olds, your metabolic age is 35, regardless of whether you’re actually 25, 35, or 45. The device or software essentially asks: “What age group does this person’s metabolism most closely resemble?”

It’s important to understand that different manufacturers may use different reference databases and proprietary algorithms.

Also, some limitations exist with metabolic age calculations. They don't account for factors like hormonal variations, certain medical conditions, medications, or genetic variations that affect metabolism. Two people with identical body compositions might still have different actual metabolic rates due to thyroid function, mitochondrial efficiency, or other physiological differences that the calculation doesn't capture.

How to Improve Your Metabolic Age?

If your metabolic age is higher than you'd like, the good news is that you have significant power to improve it. The strategies that lower metabolic age are the same ones that improve overall health:

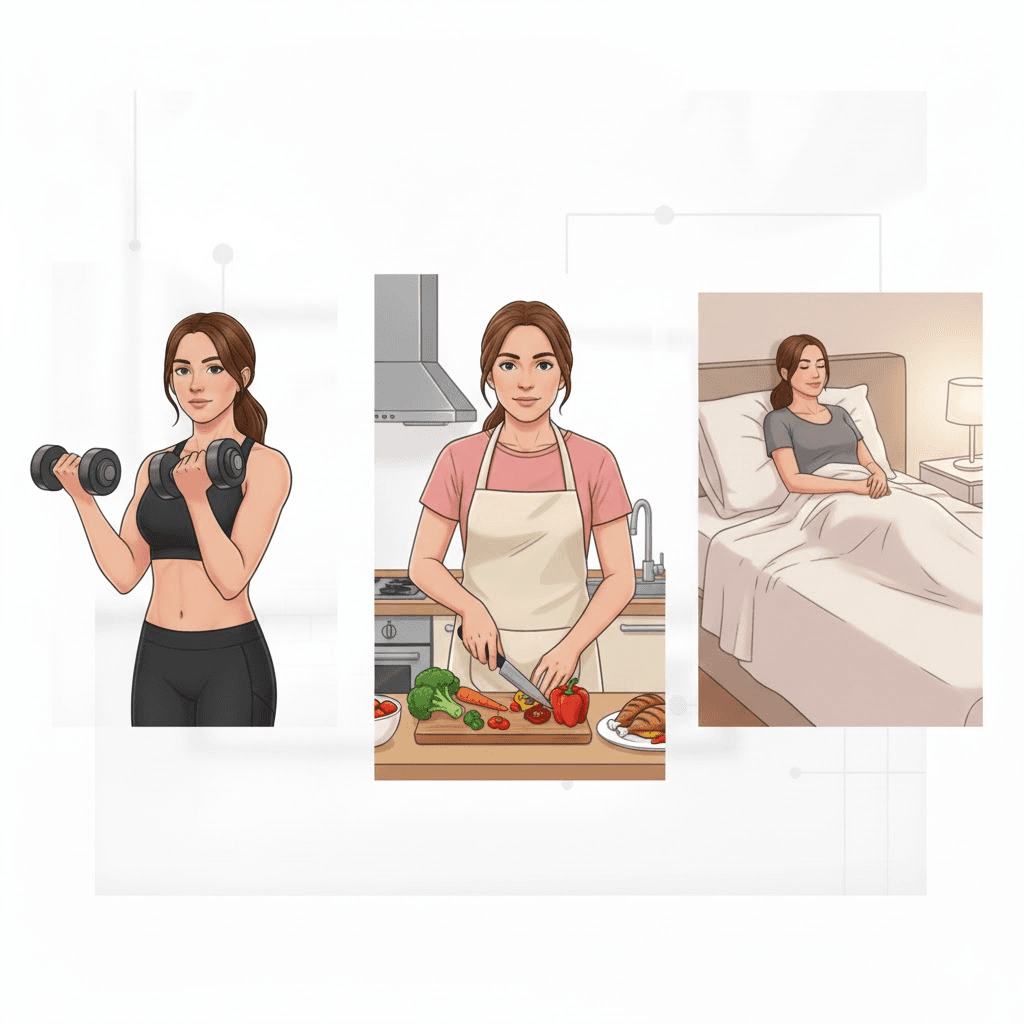

Build and Preserve Muscle Mass

Increasing your lean muscle mass is perhaps the most effective way to lower your metabolic age. Muscle tissue burns significantly more calories at rest than fat tissue does. Estimates of tissue-specific resting metabolic rates suggest skeletal muscle uses about 13 kcal per kg per day compared with about 4.5 kcal per kg per day for adipose tissue, which is roughly 6 versus 2 kcal per pound per day. Individual metabolic rate still depends on many factors, including total lean mass and organ activity.

Resistance training can play a major role in preserving muscle and supporting metabolic health. Aim for at least two to three strength training sessions per week, targeting all major muscle groups.

As you age, you naturally lose muscle mass in a process called sarcopenia, which can start as early as your 30s and accelerate after 50. Counteracting this requires consistent effort, but the metabolic payoff is substantial. Progressive overload, gradually increasing the weight, reps, or difficulty of your exercises, ensures continued muscle growth.

Optimize Your Nutrition

What you eat profoundly affects your body composition and metabolic health. Prioritize protein intake, as protein supports muscle maintenance and growth. The Recommended Dietary Allowance for protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight, which is about 0.36 grams per pound. Some people may benefit from higher intakes depending on activity level and goals, but individual needs vary.

Avoid excessive calorie restriction, which can actually slow your metabolism. Severe dieting triggers adaptive thermogenesis, where your body becomes more efficient (burns fewer calories) to conserve energy. Instead, if weight loss is a goal, focus on moderate and sustainable changes in energy intake that you can maintain over time.

Focus on whole, minimally processed foods that provide nutrients without excess calories from added sugars and unhealthy fats. Adequate protein, healthy fats, and complex carbohydrates provide the building blocks your body needs for optimal metabolic function.

Don't skip meals or go extremely low-calorie for extended periods. Consistent, adequate nutrition supports metabolic health better than dramatic restriction followed by overeating.

Incorporate Cardiovascular Exercise

While cardio doesn't build muscle like resistance training does, it supports overall metabolic health, improves insulin sensitivity, and helps with fat loss. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) appears particularly effective for metabolic benefits, alternating short bursts of intense effort with recovery periods.

Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week, as recommended by the CDC. This supports cardiovascular health, helps maintain a healthy weight, and improves your body's ability to process nutrients efficiently.

Prioritize Quality Sleep

Sleep deprivation wreaks havoc on metabolism. Poor sleep disrupts hormones like leptin and ghrelin that regulate hunger, increases cortisol (which promotes fat storage), and reduces insulin sensitivity. Chronic sleep debt is associated with weight gain, increased body fat, and muscle loss.

Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Establish consistent sleep and wake times, create a dark and cool sleeping environment, and limit screen time before bed. Think of sleep as a non-negotiable pillar of metabolic health, not a luxury.

Manage Stress Effectively

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which promotes abdominal fat accumulation and can break down muscle tissue. High cortisol also impairs insulin sensitivity and can increase appetite and cravings for high-calorie foods.

Incorporate stress management techniques that work for you, meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, time in nature, or engaging hobbies. The specific method matters less than finding sustainable practices that genuinely reduce your stress levels.

Stay Hydrated and Limit Alcohol

Proper hydration supports all metabolic processes. Even mild dehydration can reduce metabolic rate slightly. Water also helps with appetite regulation and supports exercise performance.

Alcohol, meanwhile, can interfere with muscle protein synthesis, adds empty calories, and can disrupt sleep and recovery. Moderation or elimination of alcohol often leads to improvements in body composition and metabolic markers.

Be Patient and Consistent

Improving metabolic age doesn't happen overnight. Significant changes in body composition typically take weeks to months of consistent effort. Focus on building sustainable habits rather than seeking quick fixes. Small, consistent improvements compound over time into dramatic transformations.

Track your progress not just through metabolic age measurements but also through how you feel, your energy levels, exercise performance, and how your clothes fit. These subjective markers often improve before the numbers change significantly.

Key Takeaways

Metabolic age compares your basal metabolic rate (BMR) to the average BMR of people in your chronological age group, showing whether your metabolism functions like someone younger or older.

Understanding what metabolic age means can help you interpret trends related to body composition and metabolic health.

Building and preserving muscle mass through resistance training is the most effective way to lower your metabolic age, as muscle burns significantly more calories at rest than fat.

Your metabolic age is dynamic and responsive to lifestyle changes like nutrition, exercise, sleep quality, and stress management, unlike your fixed chronological age.

A metabolic age higher than your actual age serves as a warning sign for potential health issues, while a lower metabolic age typically indicates favorable body composition and better metabolic health.

Consistency in healthy habits matters more than quick fixes when improving metabolic age, as significant changes in body composition and metabolic function take weeks to months of sustained effort.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does metabolic age mean?

Metabolic age compares your basal metabolic rate (BMR) to the average BMR of people in your chronological age group. It indicates whether your metabolism functions like someone younger, older, or the same as your actual age based on body composition and energy expenditure.

How can I lower my metabolic age?

You can lower your metabolic age by building muscle through resistance training, eating adequate protein, incorporating cardio exercise, getting 7-9 hours of quality sleep, managing stress effectively, and maintaining a healthy body composition with less body fat and more lean muscle mass.

What is the difference between metabolic age and chronological age?

Chronological age is simply the number of years since you were born, which advances steadily and cannot be changed. Metabolic age is a functional measure of how efficiently your body burns energy, which can be improved or worsened based on lifestyle choices and health habits.

Is metabolic age an accurate indicator of health?

Metabolic age provides useful insight into metabolic health and body composition, but it's not a standardized medical diagnostic tool. Different devices may give varying results, and it should be considered alongside other health markers like blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels.

Can you reverse your metabolic age?

Yes, metabolic age is changeable and responsive to lifestyle interventions. By increasing lean muscle mass, improving nutrition, exercising regularly, and adopting healthy sleep and stress management habits, you can effectively lower your metabolic age over time with consistent effort.

What causes a high metabolic age?

A high metabolic age typically results from excess body fat, insufficient muscle mass, sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition, inadequate sleep, and chronic stress. These factors reduce your basal metabolic rate, making your metabolism function like someone older than your actual age.